“Get the fundamentals down, and the level of everything you do will rise.” - Michael Jordan.

The fundamentals are still telling us to be careful of risk-taking. Stay Vigilant

“Get the fundamentals down, and the level of everything you do will rise.” - Michael Jordan. Being from Chicago and being able to enjoy Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls during my 20s has clearly biased me toward who is the GOAT. I saw someone bring the city together like no other single person. Living abroad in 4 different countries during his run, I got to see what a truly global phenomenon he was. It is hard to judge who the GOAT now as we are all burdened by recency bias, not the least of which comes from watching current players, but also our opinion of MJ himself after “The Last Dance”. That said, it is very hard to argue that the guy didn’t work his tail off in mastering the fundamentals, which opened up a world of opportunity for him.

In investing, we are always talking about ‘the fundamentals’. I recall vividly speaking to analysts and traders who would tell me ‘such and such isn’t moving on the fundamentals’ to which I would always reply ‘it is moving on fundamentals, just maybe not the ones you are watching.’ Risky assets move for a variety of reasons. Often it is about the macro fundamentals that are shifting. Sometimes it is about the fundamentals that drive a certain investment style into or out of favor. Nowadays, about 4 times a year, it is about the idiosyncratic fundamentals. We need to be aware of how all of these are moving. These is why looking across the globe for the ‘fundamentals’ is always the first step in the process. I know when I ran equity long/short, I would never be short something with good fundamentals or long something with bad fundamentals. Even if the other parts of my process - supply/demand and catalysts - suggested it. I would be flat instead. This was akin to Warren Buffet’s comment that when a good management team meets a bad business, the bad business will win. However, just because something had good fundamentals doesn’t mean I would always be long, or if bad fundamentals I would always be short. In the overall market, we need to understand at the core what the trend of risk will be and the only way to do that is to look at the ‘fundamentals’. So let’s do so.

Valuation

For individual assets, I use valuation as a measure of sentiment. However, when looking across assets, I look at relative valuation to get a sense of how an asset allocator, that drives decisions at the core, and which has a longer holding period, will assess the various markets. Too much of our daily banter has to do with what fast money traders think. They aren’t moving the trillions of dollars that give the tailwind, or the headwind, to assets. The first chart I show compares the P/E of the equity market to a "‘P/E” of the credit market, which I calculate by looking at the inverse of the corporate bond yield. These assets both have credit risk and both have beta risk. An allocator can choose where it wants to allocate this risky asset exposure between the two. The decisions are sticky once made. You can see that equities were preferred in the 90s up until the bubble in 99/00 with the SPX basically trading at a 12 P/E turn premium to the credit market. Growth was key and equities are more levered to growth. Post the Great Financial Crisis, the story has been completely different For the last 10 years, there has been a preference for risky asset exposure via the credit market and we see that the bubble in credit in 2020 almost got to the same extreme as equities in ‘99. There was a 10 P/E turn premium for credit over equities. This has normalized somewhat but it would still suggest there is more positioning, and therefore more risk, in the credit market than the equity market. We need to watch the credit market for clues as to when the end of selling pressure happens.

On this front, this is not a particularly compelling chart of the riskiest portion of the credit market:

We can also compare the equity market to the sovereign bond market and one way to do this is to look at the earnings yield of the SPX vs. the 10 year US Treasury yield. This was a favorite of Alan Greenspan which is why it is called the Fed Model. There are all sorts of short-comings to this approach, however, stepping back, one can ask if one is being compensated enough to take on the extra risk of an equity investment. Very roughly speaking, the average is about 2%. However, over periods, we can get about 4% away from this. In the tech bubble, the yield on equities was at a discount to bonds. It was clearly a bubble. However, post the GFC and almost during Covid, we got to 6% yield difference which is again about 4% away from the norm. At this point, given the move in the 10 year as well as the move in equities, we are about average and so neither asset stands out. However, using this metric can help us see when either asset is getting a bit over-extended and for the entire post GFC period, equities have traded ‘cheaper’ than average relative to bonds, even when everyone says the valuation is a bubble.

Overall, the equity market does not appear to be bullishly extended right now but also doesn’t scream that it is getting too cheap. In order to get more excited for equities, I would want to see a bottom in both credit and sovereign bonds to establish a floor level for equities on a relative basis.

Economic Trend

One cannot look at the fundamentals of risk without also looking at the trend of the economy. There are so many crosscurrents in the economy now it is very difficult to ascertain what we should be doing. It is because of this uncertainty that risky assets are struggling. As we get more clarity on this front, we can start to feel more comfortable to take risk. For me, the key metric to watch has always been the yoy changes in the ISM. It fits well with yoy changes in the SPX. You can see relative to both measures, the GDP changes simply lag meaningfully. That is one reason, besides the fact it will be revised two more times, that I don’t even care about GDP. It came out this week and was really a non-event in my book. The information is in the ISM because changes here tells us what to be excited or nervous about in stocks. Right now, ISM is still pointing to lower stocks.

A high-frequency indicator that is relative new but gets a lot of focus is the Atlanta Fed Nowcast. I don’t know if there is a great deal of new information here, but it is also leading and pointing to a slowdown in the economy. Noticeably, it is not pointing to a recession.

How do we anticipate the ISM though? The ISM is coincident with the SPX but we would ideally like to have an idea of where both are going. In order to get a feel for where the ISM is going, we can look to the internals of the number. When the ISM comes out, we are also given information on new orders and inventories. The ratio of this has good leading properties of the ISM itself and it is intuitive. When inventories have been built up too much, such that new orders fall on a relative basis, there is going to be a slowdown in the economy. The opposite is true which is what we witnessed in 2020-2021. Right now, this measure is suggesting more pain ahead for the ISM, and therefore for risky assets.

Another way we can try to anticipate the ISM is looking at all of the regional Fed surveys. Each Federal Reserve region puts out a survey of how business in its district is doing. These come out a week or two before the ISM. It isn’t a major head-start but better than nothing. It is a bit of a mixed bag, but in general it is pointing to lower levels, especially with the latest Empire (NY Fed) number. One has to feel this is how the market will be leaning.

The other story right now is inflation. In the graph below, the yellow line is CPI, the green line is ISM and the blue line is the 10-year. You can see that right now the 10-year yield is conflicted between a rising CPI and falling ISM. You can also see that the notion that a high CPI will naturally pull down growth is only something we have seen in the 70s, as nothing in the last 20 years suggests it will. However, if we are in the 70s, you can see that levels of CPI that we are seeing were consistent with growth slowing. Was it a different time than now?

Inflation is a mindset. Yes, we had the highest money supply growth in the history of the US post Covid. We also had historic fiscal stimulus. All of this served to form people’s opinions on inflation - it meant workers were demanding more money to go back to work and it meant those who were ordering were willing to pay higher prices. We see that while the money supply in blue has fallen, the CPI in green continues to rise. This means that the yoy change in Raw Industrials prices in yellow is still positive and the change in average hourly earnings in pink is positive and rising. Conversations with C-suite executives in chemicals, steel and energy all confirm to me that the prices of these raw industrials are going to continue to move higher. Wages are most likely going to as well. Can we really think with this backdrop, prices will just naturally fall? Or do we need a recession to get us there?

The yield curve is also trotted out as an indicator of impending recession. First, the only yield curve that matters is the 2y10y. This talk of 5y30y is data-mining. I get it, trying to keep out the Fed distortion, but the series has neither a long history nor a good predictive power. I always ask students why the yield curve should be an indicator. They figure out that it would through the transmission of credit in the economy. Financial firms borrow short and lend long. When the curve is flat, there is less incentive to extend credit. For most financial firms, the curve that matters is the one in blue, the 3m10y. These firms can now found themselves through deposits as well as the Fed (post GFC). Only FinTech firms need to go to the market. Previously, wholesale banks would have to but these firms all blew up in the GFC. Long story short, the 2y10y is still suggesting times could be tough. However, even when it has inverted, it has been with long and variable lags of 6 months to 2 years. This suggests that the message from the yield curve is that a recession is not a 2022 event.

We want to look not just at the US though. China is the 2ng biggest economy in the world and a major driver of risk. To get a gauge of anticipating the Chinese PMI in white, I look at hot rolled steel prices in orange, and at the Li Keqiang index which looks at bank loans, rail freight and electricity prices. All of this suggests some more trouble ahead for China, and with the lockdowns in Hong Kong and Shanghai (with others to surely follow), this should not be a surprise.

The end result for the economic trend section is not overly positive. There are really no indicators that suggest things will get better. The best we can hope for is that things do not deteriorate into a recession in 2022. Likely, it looks like the recession is a mid 2023 event. However, this is still not the best of backdrops for risky assets.

Central bank liquidity

Looking across the 4 major central banks (US, EU, China, Japan) we can see that balance sheets are starting to rollover some. It is still not particularly contractionary and one wonders how much it would continue to reduce in the US if things got difficult. With events in the Ukraine, the ECB has not really started to reduce the balance sheet at all. We know Japan is actually going the opposite way and is easy policy by buying more assets. China will surely be easing at the margin with the crisis unfolding there. So while this global central bank balance sheet growth has been a major driver of risk, and the market is worried about the QT from the Fed pulling the rug out from under risk, with the other 3 central banks either in neutral or easing, I would expect a continued accommodation from the balance sheet.

However, on the rate front, global central banks led by EM central banks have been easing for a year. The lagged effect of this points to lower economy ahead:

Also, China is easing aggressively using a number of tools:

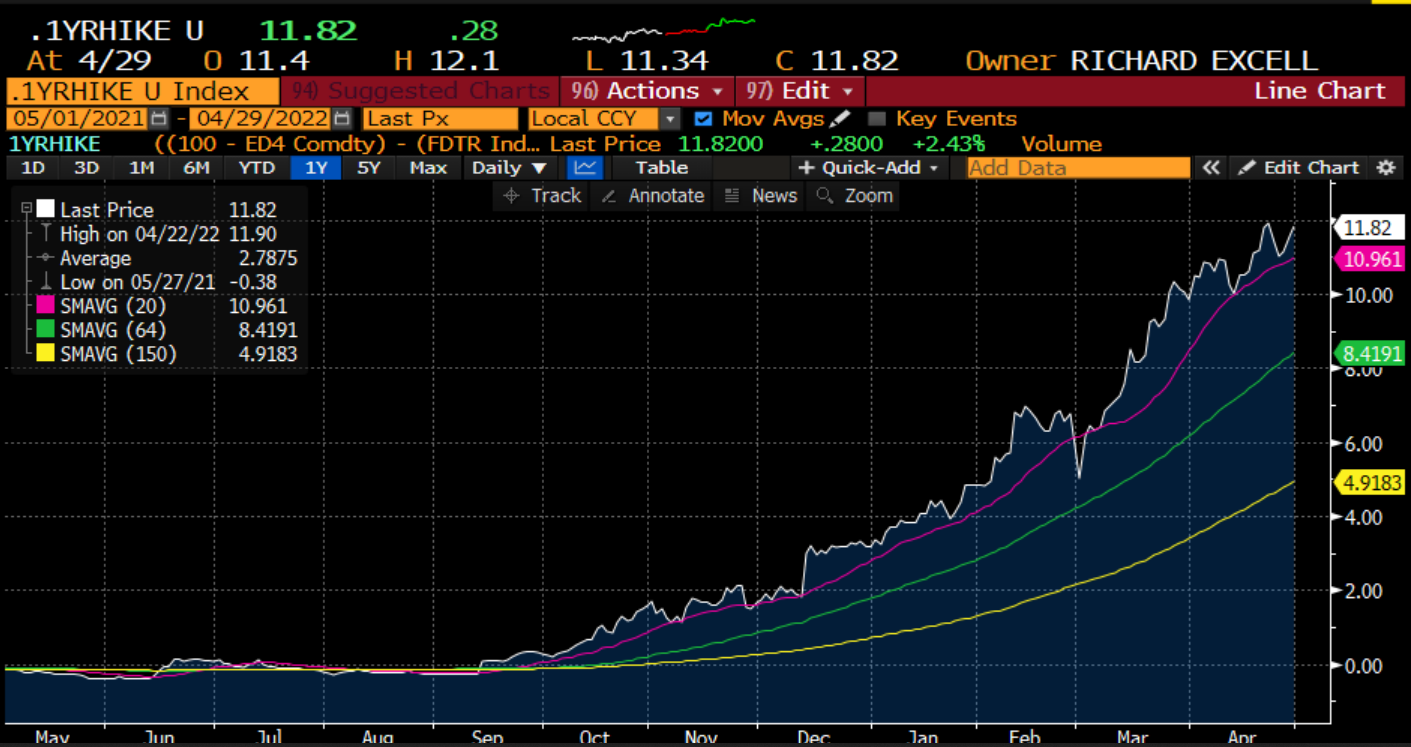

However, the Fed is expected to tighten aggressively. The number of hikes priced into the next year is now 12.

Pulling this together, I think the central bank category is a bit more neutral for risk. It had been negative with the Fed slowly removing liquidity and global central banks already having done so. However, now, China and Japan are easing. The Fed expectations are hawkish, but reality has not matched that yet. In total, therefore, I think this is a bit more neutral.

Velocity

I just want to include one more chart. We know from the quantity theory of money that Nominal GDP (P*Y) is equal to money growth * velocity (M*V). We spoke of money growth above but without an idea of velocity, it is difficult to know what this means for nominal GDP. Post GFC, velocity (demand for money) was very low which meant money growth had a low impact. I try to anticipate what demand for money will be. I look at the home purchase index in pink, small business optimism in yellow and commercial and industrial loans in blue. Only the latter is finally picking up while the other two are falling. Thus, in the US, not only is money growth falling but the demand for money is falling too. This does not get us a good forecast for nominal GDP going forward. With inflation staying high, that means real GDP expectations should be even lower.

With real GDP already slowing (blue) and expected to slow further, this does not paint a good picture for the growth of S&P earnings going forward:

Where does this all leave us? Not in a great spot to be honest. The relative valuation of equities is not that bad relative to credit or bonds, however, both of those are falling precipitously right now. Until we can get comfortable with a bottom in those markets, there is no reason to think there will be a bottom in stocks.

The outlook for the economy is not overly positive. The best I can say is I do think we will not get a recession in 2022, with one more likely in 2023. However, that does not mean the economy won’t be slowing, just maybe not as much as others fear. Still not great.

Central banks are starting to change their tune. While the Fed is starting to (and expected to be) quite hawkish, China and Japan are going in the opposite direction and the ECB is on hold. The fear of global central bank balance sheet shrinkage has not yet happened.

However, consumers and companies are not demanding this money. The forward look on nominal and real GDP is not positive as a result. This does not paint a good picture for S&P earnings and therefore for stocks overall.

In aggregate, this is a negative picture for risk in the market. There is a time to say things have maybe good too far, but now is not that time. The fundamentals are telling us the bottom is not in for the markets yet.

Stay Vigilant